Who gets to decide which pieces of art should be made? That’s the question I’ve been thinking about since Ryan Murphy’s limited series Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story dropped on Netflix. This question seems to be a big part of our zeitgeist, as evidenced by social media’s excoriating backlash against the show in which members of the public and even critics raise the question of whether Murphy’s 10-episode deep dive on the Wisconsin serial killer should have ever been made at all.

Some pre-loaded distaste for a series about the most famous serial killer of the last half century is expected, but the outcry against Dahmer seems particularly inexplicable in the United States, where true crime “entertainment” is more popular than ever, and two of the most downloaded podcasts of all time are Serial and Doctor Death.

One has to wonder what the Dahmer backlash is really about, especially when it seems that a huge amount of people expressing their disgust for the series are objecting to the show’s existence rather than, say, its artistic execution. Looking at the reviews on Rotten Tomatoes (as of this writing hovering at a dismal 50% favorability) even critics seem to have come to the show with knives sharpened.

I was dubious myself before watching the series; to be frank, I wasn’t sure there was a new or interesting take to be had on Jeffrey Dahmer, and I’m pretty hit and miss when it comes to Murphy’s output in general. But even when questioning the nature of a project I like to approach any film or series with an open heart and mind—something I learned from Roger Ebert. So, when I pressed play on the series, I might have been circumspect, but I didn’t discount the possibility of being surprised.

I had anticipated a dark dive into what made Dahmer tick along with your requisite ghoulish sequences of murder and mayhem. I had also anticipated some effort to understand Dahmer by delving into his family life and childhood. While Dahmer has all of this (in spades) what surprised and impressed me most was the amount of time Murphy and crew spent illuminating the lives and personalities of the victims. While this aspect of the series does make the murders very hard to watch (a strange complaint I’ve seen on Twitter), perhaps it’s time to remember that murder should be hard to watch. In conversation about the state of our society we hear endless complaints about how modern entertainment has “desensitized” us to violence and killing. In the public’s complaint about murder being uncomfortable to watch, perhaps we can read an effort on Murphy’s part to re-sensitize us to it.

One of the main arguments against the creation and release of Dahmer is that the show is exploitative—in that it tells the stories of murdered people for profit. How strange that this argument would be applied to this series, of all serial killer projects, when what the show does as well as anything is humanize the victims and their families—something rarely attempted, let alone accomplished, in such productions. Even a serial killer masterpiece like David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) doesn’t spend time giving you more than a cursory sense of the victims whose deaths are depicted. There’s also the “serial killer fatigue” faction that believes we simply don’t need any more stories about people so heinous. But if that’s the case, where is the cutoff? Do we stop at terrorists and dictators, or do we stop at gangsters and dirty cops? Should we stop making films and series about oppressive regimes, genocide, wars, or any number of true stories about harm and suffering? Almost every important story is painful to someone, somehow. But what Dahmer gets so right—in a way that feels groundbreaking—is that it is very much about the humans that were harmed. In fact, I can’t think of any film or series on the subject of serial killings that invests so deeply in the lives of those that were lost.

The first episode, which depicts Dahmer’s attempted murder of Tracy Edwards, gives so much time to the intended victim that you feel not only his fear, but can see the inner workings of his mind as he tries to figure out a way to escape. Tracy (played brilliantly by Shaun J. Brown) is not simply a marker on Dahmer’s timeline. He’s sweet and funny, playful, industrious, and on this particular night, willing to pose for Jeff Dahmer’s camera to help make his newly-raised rent. We meet Tracy, just as Dahmer did, at a gay club where we see him hanging out and having a beer with friends before he makes the fateful decision to go home with Dahmer. In the arc of one episode we get to see Tracy’s sense of humor, his smarts, and finally his desperation. What makes the episode so terrifying is that we have a sense of Tracy as a full human being by the end of it. Had we not gotten to know him, the episode would have been nothing but a ghoulish undertaking—something Murphy eschews throughout.

The first episode, which depicts Dahmer’s attempted murder of Tracy Edwards, gives so much time to the intended victim that you feel not only his fear, but can see the inner workings of his mind as he tries to figure out a way to escape. Tracy (played brilliantly by Shaun J. Brown) is not simply a marker on Dahmer’s timeline. He’s sweet and funny, playful, industrious, and on this particular night, willing to pose for Jeff Dahmer’s camera to help make his newly-raised rent. We meet Tracy, just as Dahmer did, at a gay club where we see him hanging out and having a beer with friends before he makes the fateful decision to go home with Dahmer. In the arc of one episode we get to see Tracy’s sense of humor, his smarts, and finally his desperation. What makes the episode so terrifying is that we have a sense of Tracy as a full human being by the end of it. Had we not gotten to know him, the episode would have been nothing but a ghoulish undertaking—something Murphy eschews throughout.

Even more significantly, Dahmer devotes nearly an entire episode to victim Tony Hughes (a heartbreaking Rodney Burford). Over that hour, we learn that Hughes was deaf from birth, but filled with a wondrous spirit that refused to allow him to be kept down by a society that marginalizes not only the deaf, but gay men and people of color (all of which Tony was). For me, the most compelling scene in the Dahmer series is a conversation in American Sign Language between three friends—all gay deaf men—sitting at a table in a pizza joint talking about their lives and what they hope to do with them. It’s a profoundly effective scene that feels more like eavesdropping on real people than it does a dramatization. The sequence is shot mostly without sound, and it’s absolutely beautiful.

These are men who are often not fully seen in real life or even portrayed on screen, especially not in the early ‘90s—but here they are, hanging out, living their lives in the shadow of death (not just the shadow of Dahmer, which they couldn’t have known, but the then-prevalent AIDS crisis), and still being funny, affecting, thoughtful. The series didn’t need to showcase these men in such a way, but it’s sequences like this (of which there are many) that show us Murphy’s equal and genuine interest in Dahmer’s victim’s lives and their world—not just what happened to them and when. To my mind, that’s a brave choice deserving of respect, especially considering that serial killer dramas can get by just fine, and make a lot of money, appealing to the lowest common denominator.

But the show’s thoughtfulness doesn’t stop there. Dahmer also takes a deep interest in illuminating the aspects of society that allowed Jeff Dahmer to get away with killing people as long as he did—namely that certain groups of people are not well-served by law enforcement. Dahmer was reported, multiple times, by his then-neighbor Glenda Cleveland (played in the series by a terrific Niecy Nash). But Glenda was a black woman in an underserved community and she wasn’t taken seriously. Time and time again we watch her call the police to warn them about the awful smell emanating from Dahmer’s unit, as well as the screams she hears through her vent. Glenda’s phone calls and desperate pleas illustrate with brutal force and feeling how women’s voices, and black women’s voices especially, are so often rendered a complete zero.

At no time is the racism, homophobia, and chauvinism endemic in the police force more obvious than when officers are called to investigate a drugged, undressed and wounded 14-year-old Laotian boy, Konerak Sinthasomphone, collapsed outside of Dahmer’s apartment complex. Ignoring the protestations of Glenda Cleveland, the officers return the boy to Dahmer, who claims the boy is his lover. It’s a stunning moment that seems impossible to believe, but when the actual 911 call is played at the end of the episode we hear just how chillingly real police disinterest was when it came to this community. Many years ago, author Ralph Wiley wrote a book called Why Black People Tend to Shout. In watching the plight of Glenda Cleveland, that title came painfully to mind. Black people shout for the same reason anyone else does: because they feel like they are not being heard. Even so, Glenda Cleveland shouts as loud as she can, and she is still not heard.

At no time is the racism, homophobia, and chauvinism endemic in the police force more obvious than when officers are called to investigate a drugged, undressed and wounded 14-year-old Laotian boy, Konerak Sinthasomphone, collapsed outside of Dahmer’s apartment complex. Ignoring the protestations of Glenda Cleveland, the officers return the boy to Dahmer, who claims the boy is his lover. It’s a stunning moment that seems impossible to believe, but when the actual 911 call is played at the end of the episode we hear just how chillingly real police disinterest was when it came to this community. Many years ago, author Ralph Wiley wrote a book called Why Black People Tend to Shout. In watching the plight of Glenda Cleveland, that title came painfully to mind. Black people shout for the same reason anyone else does: because they feel like they are not being heard. Even so, Glenda Cleveland shouts as loud as she can, and she is still not heard.

One could make the argument that Jeff Dahmer is just the linchpin the series uses to showcase a myriad of societal ills. Issues of race, class, and sexuality are all focused on with a surprising degree of empathy and intellectual integrity, but above all the show is about who is listened to, and why it matters. Dahmer doesn’t really seek to entertain, it seeks to inform, and often does so remarkably. Way back in 1978, long before the incident when police trusted Dahmer over Glenda Cleveland and hand-delivered a young boy to a killer, Dahmer was pulled over for drunk driving (with his first victim in trash bags on his back seat). Not wanting to be this young man’s first run-in with the law, the officers let him go. In 1989, two years before being arrested for murder, Dahmer would plead “no contest” to molestation of a child (not unimportantly, a child of immigrants), but the judge, not wanting to ruin a promising (code:white) young man’s life, gives him a slap on the wrist and sets him up with a work-release program.

The series shows minorities shout to be heard while Dahmer mumbles his way through life, and it is the mumbling that prevails. We are shown how Dahmer was given the benefit of the doubt time after time, given chance after chance, opportunity upon opportunity, and what we finally come to understand is that Dahmer’s “success” as a serial killer didn’t have much to do with Dahmer at all. He didn’t get away with killing people because he was especially smart (he wasn’t), or charismatic (just the opposite), or careful (not at all), but because he was white. Dahmer was white and his victims were mostly from black or gay communities—populations that the police simply didn’t prioritize when they went missing. The show is a stunning condemnation of the powers that be.

I actually think the full title of the series: Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story undercuts what Murphy and his team have accomplished. To label Jeffrey Dahmer a “monster” is far too easy and lets society off the hook in a way the series does not. While Dahmer’s murders are monstrous, they were committed by a human being. Many overly-virtuous critics have taken issue with the series’ humanization of Dahmer. And you know what? They are right. He is presented as a real person, and as we are taken through the details of Jeffrey Dahmer’s life, we see a number of factors that may have played a part in the development of his sick compulsions. While carrying him to term, his deeply depressed mother was dangerously overmedicated. As a young boy he may have suffered brain damage from too much anesthesia during a surgery. His parents fought constantly, which left him in a constant state of insecurity and fear of abandonment. He discovers his sexuality at a time when it was not acceptable to be gay. What was born from this set of circumstances was a man so damaged and alone that his twisted fantasies were all he had, and disastrously, he acted upon them. But while the show humanizes Dahmer it does not attempt to completely explain him, and nor does it in any way forgive him.

Seeing Dahmer as human is absolutely central to the project, because only when we see Dahmer as human, not as a “monster,” can we see him for what he truly was: a fuck up and a failure. He was deeply disturbed and incredibly dangerous, but he was also a careless, urge-driven alcoholic. He was sloppy. He made mistakes. Only when we understand the very human failings of Dahmer can we see the painful reality that he should have been caught much sooner. Dahmer was able to get away with murder because our society—instead of letting him fail and arresting him for drunk driving, or putting him in jail for molesting a child—continually propped him up and enabled him to continue killing. That truth is what this series illustrates so well, and I’ve never seen such a new, compelling, and clear-eyed take of the Dahmer story.

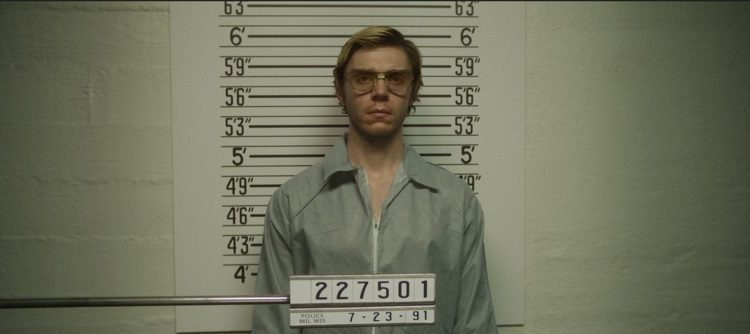

This presentation of Murphy’s wouldn’t have been possible without Evan Peters’ brilliant performance, who plays Dahmer as being deeply weird without making him the least bit charismatic. At no point does he give Dahmer any Lecter-like flourishes (something that many actors wouldn’t have been able to resist). Evan Peters’ Dahmer is drained of any sense of the colorful, which is appropriate, because the real Dahmer was hardly a scintillating personality. A colorful performance would have distracted from the larger intention of the project. This serial killer is a dull blade, a blunt instrument, a cold, stunted, and dangerous person.

But this series decided to be about much more than a killer. Instead, what Murphy has created is a dark yet very real social commentary, one that places as much blame on the society that gave him the free pass as it does on Dahmer himself. In a typical dramatization we normally see serial killers through the eyes of the cops or detectives. Murphy’s series makes us see Dahmer through the eyes of those he harmed. So when I hear someone say that the new Dahmer series glorifies violence, or that it glorifies Dahmer, or that it disregards the victims, I really have to ask:

Did you watch it?

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)